The Communal Effects of Racism on Mental and Physical Health

November 28, 2017

“I don’t have a gun. Stop shooting.” Michael Brown, age eighteen. August 9, 2014.

“Please don’t let me die.” Kimani Gray, age sixteen. March 9, 2013.

“What are you following me for?” Trayvon Martin, age seventeen. February 26, 2012.

“I can’t breathe.” Eric Garner, age forty-three. July 17, 2014.

“I wasn’t reaching.” Philando Castile, age thirty-two. July 6, 2016.

“It’s not real.” Tamir Rice, age twelve. November 22, 2014.

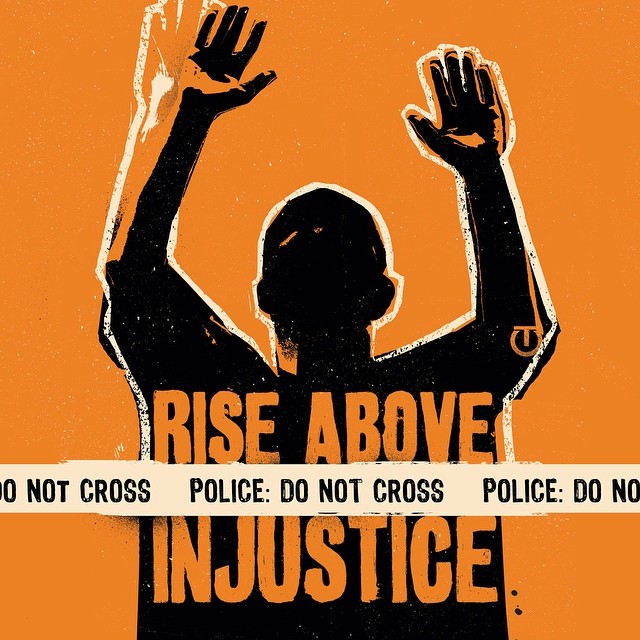

These could be the names of our brothers, our sisters, our classmates, our neighbors, our co-workers, our friends, our family. They could be the bagboy at the market who puts away your groceries or the doctor who gives you your yearly check-up. Their names could be on a teacher’s roll call list or read off at a high school graduation, but instead, they’re etched onto tombstones, just added to another statistic regarding African American victims of police brutality. These are people in our community, and if they’re not in our community, they’re in the community next to ours, or the one next to that, or in the state over, or across the country. Regardless, they are the men and women that make up this beautiful, diverse melting pot of the United States of America, and they are being killed on our own soil, by our own people. The stories are devastating. The deaths are inundating. And time and time again, we ask ourselves “How?” “Why?” and we grieve. And the country moves on. But the wound of a tragedy does not heal so easily when this occurs in the streets of your childhood home, and we are seeing the lasting negative effects of these murders within the communities they exist in. Ultimately, areas subjected to racial prejudice and examples of police brutality experience corresponding issues surrounding mental and physical health as well.

According to a study conducted by Naa Oyo and Melody S. Goodman of The American Journal of Public Health in which two primarily black New York cities were tested for both levels of personal discrimination based on race and personal relationship with race, it was concluded that over time, a poor relationship with one’s race –affected by racial discrimination—directly correlates to higher levels of depression and psychological distress. These results were ubiquitous amongst both primarily African American communities, emphasizing racism as a stressor and contributor to mental health concerns. Imagine the anxiety of a black man walking down the street knowing his fellow black man was shot on the same sidewalk. Day after day, these worries plague the African American community, and over time, such angst is translated into poor self-image and signs of poor mental health.

The countless unarmed African American yearly deaths by police simply crafts an unsafe environment for people of color in their own towns. Think petrifying fear walking down to the corner store. Think paralyzing terror each time you’re pulled over by a cop. Think about constantly being afraid for your own life each day you simply try to exist. This distress not only takes a toll on people mentally, but also physically.

Yeonjin Lee, Peter Muennig, Ichiro Kawachi, and Mark L. Hatzenbuehler’s study from The American Journal of Public Health further substantiates this in exploring the increasing mortality rates in areas highly concentrated with racial prejudice. As suggested by their research, social-capital on a community level is the linking force between racism and deaths, with poor societal relations heightening the tensions. While both races experience higher mortality rates when surrounded by social prejudice, “the results indicated that living in a community with higher levels of anti-Black prejudice increased participants’ odds of death by 31%” (Lee, Muennig, Kawachi, Hatzenbuehler 4).

So is there a practical solution? Communities are struggling, specifically primarily-black communities, a minority group which contributes to approximately 13.5% of the population. That’s a large selection of people, Americans nonetheless, to disregard mentally and physically. Because these issues directly correspond with health, it would be best to treat them as such. Jane Ellen Stevens of the Technology Review compares the spread of violence to the spread of AIDS, which basically galvanized society into employing further research and, altogether, raising awareness. Both are societal problems that are so blatant they cannot be ignored, yet racial violence is often overlooked despite the evidence of its effects on health.

The longer these salient issues are ignored, the deeper the metaphorical and literal bullet wound grows, polarizing our communities so much that the real problems at hand are ignored for political disparities—hence the vicious cycle that African Americans find themselves stuck in. They’re on a stationary bicycle that’s going nowhere while their brothers and sisters are being killed in front of their eyes. America, it’s time to mend the wound. It’s time to patch up the communities of people you’ve injured and stitch them back into our offered empathy. It’s time for the nation to really rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed. All men are created equal. Let us start to act like it.