Every high school student has homework, from after-school chemistry lab work to being assigned an imparfait worksheet in French, but the drive to complete it is another question. When students get assigned homework, what is the first thing that goes through their minds? More importantly, what separates the top students, those who excel not just in homework but also at tests, quizzes, and essays, from the rest?

I used to think it was motivation. For the most part, it was. Motivation was a temporary force that drove me to complete tasks, especially when I rushed through assignments. If I pushed myself hard enough using a quick spark of motivation, it could get me through my homework. For a while, it worked, especially for subjects that came naturally to me. Then came math. At first, it was basic logic, then it grew harder, and the motivation that was supposed to carry me through crumbled. “Everyone struggles with something, right?” I thought. “Come on, I can do this,” but the phrase had no purpose. Math made me question whether I was even capable at all. I felt like I lost hope, not just in my schoolwork but in my abilities.

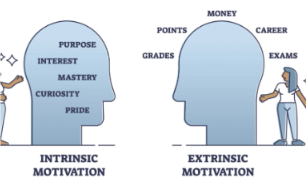

That’s when I realized something critical: my understanding of “motivation” had been incomplete. Psychologists often categorize motivation into two types: intrinsic motivation, which comes from “internal desires, someone who’s driven to accomplish a goal”, and extrinsic motivation, which comes from “external awards, someone who is motivated by what they receive”. Until then, I relied on extrinsic motivation, pushing myself through tasks just to complete them. Yet, the students who excelled in numerous subjects were driven by something more profound. They had intrinsic motivation: improving, challenging the mind, and growing.

According to the National Institute of Health, intrinsic motivation has a stronger impact on “enhanced learning, creativity, and affective experience”. When motivation, primarily intrinsic, is missing, the effects become apparent. Procrastination is easy without a sense of purpose or rewards to make a task feel meaningful. Over time, this lack of motivation can lead to lower standards in academics, weak self-esteem, deep psychological problems, and even depression.

Recognizing this made me rethink my mindset. I began to see homework as an obstacle to overcome and an opportunity to shape into the kind of learner I want to become. Since shifting my perspective, even math has become a stepping stone in developing my growth mindset.

Whether driven by intrinsic or extrinsic goals, developing habits plays a crucial role in achieving success. But here’s the thing, it’s not an immediate transformation. Motivation doesn’t always come easily. Building habits takes time, starting with small, setting achievable goals, and celebrating the little wins. Consistency over time lays a strong foundation, like building a house, brick by brick.

This is where dopamine steps in to uplift one’s mood. From the Cleveland Clinic, “dopamine plays a role in many important bodily functions, including movement, memory, and pleasurable reward with motivation.” Small celebrations release endorphins and dopamine, creating feelings of reward and motivation. But while dopamine gives us those rewarding bursts, lasting motivation doesn’t rely on one chemical to shift the mood. It’s built through momentum, forming habits that ingrain in your mind and are natural and automatic.

In this sense, discipline, “training that corrects, molds, or perfects the mental faculties or moral character,” becomes essential. Discipline is the ability to control impulses that tempt you to give up, and consistency is sticking to an action over time. Even simple routines, like getting up to brush your teeth as soon as the alarm rings, build on a strong mental state that makes larger goals achievable. A good example of discipline is being in the military. Discipline in the military is used to maintain order, ensure personnel obey, and instill high standards and accountability. Over time, discipline becomes self-discipline for many.

But even discipline and habits aren’t enough by themselves. Lasting motivation also depends on the environment we create around us. Sometimes distractions, whether it’s constant noise, doom scrolling, being surrounded by friends who don’t seek our best interests, or have different goals, can subtly keep us off track. Staying motivated comes from making intentional choices about where to allocate our energy and time. A supportive environment amplifies these factors and can help us in how we perceive ourselves.

This strong motivation comes from our identity. Instead of “I want to pass my math class,” it becomes “I am someone who challenges myself to grow, so I’ll work harder to achieve an A.” Psychologists call this identity-based motivation–when actions combine with identity, it feels natural and more meaningful. Growth stops feeling like a mandatory chore and emerges as a responsibility. When someone views challenges not as threats to their intelligence but as opportunities to grow, you know they have developed a growth mindset.

Ultimately, lasting motivation is a structure that one builds over time. It derives from the habits we form, the discipline we sustain, and, most importantly, the identity we hold. Even math, the subject that still troubles me, became a part of that foundation. Every assignment completed, every obstacle we must overcome, isn’t just a task; they’re bricks laid in cement. You can achieve greatness; it just takes one challenge at a time.