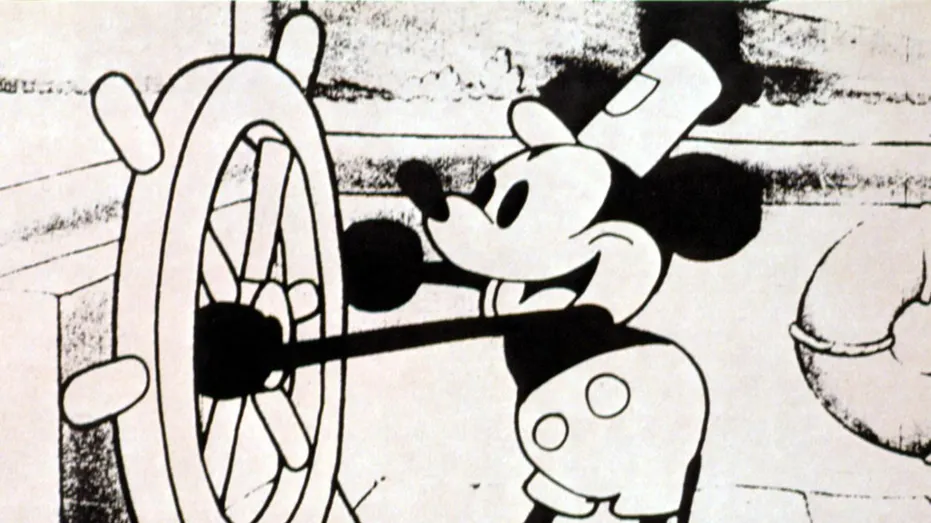

In an ideal world for entertainment companies, the rights to a property – and all potential profits it may bring in – can be exclusively yours forever. That being said, such a world doesn’t exist; instead, all intellectual property makes its way to the public domain, at one point or another. No character can avoid this – not even Mickey Mouse, whose earliest depiction, Steamboat Willie, entered the public domain last year.

This hasn’t stopped Disney Entertainment from trying to hold on to its golden goose. Recently, the company refused to relinquish the iconic mouse design at Morgan & Morgan’s request. This American law firm sought to use the character in an advertisement. In retaliation, the firm filed a lawsuit against Disney, which is still ongoing.

The Background Information

First appearing in the 1928 short “Steamboat Willie”, the titular character is best known as the first version of Mickey Mouse to appear on film. At the time, Disney was expected to have sole ownership for 56 years, but it was able to extend their ownership twice to 95 years from the year the short aired. By the 95-year mark, in 2024, Disney couldn’t do it a third time, and Steamboat Willie could now be used freely.

That doesn’t mean there weren’t any limits to how one could use the character. For one, only Steamboat Willie is in the public domain – the laws don’t yet apply to other variations of the character, such as Mickey Mouse himself, and wherever else he’s made an appearance. In addition, while copyright law no longer applies to this first version, the trademark does, and can last indefinitely. Copyright protects the work and the creator’s rights to it. Still, a trademark protects the brand and its reputation – that means if you produce a work that paints a negative image of a company’s brand, risking its reputation, you could be liable for a trademark infringement suit.

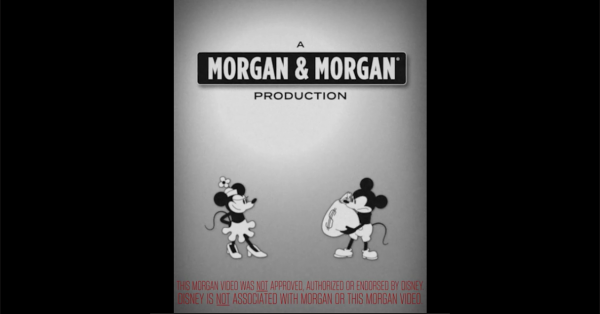

Morgan & Morgan was aware of this when creating their ad campaign, which featured Steamboat Willie getting into a car accident and having to pay Minnie Mouse for damages. “ In a disclaimer and throughout the video, it reads: “THIS MORGAN VIDEO WAS NOT APPROVED, AUTHORIZED, OR ENDORSED BY DISNEY. DISNEY IS NOT ASSOCIATED WITH MORGAN OR THIS MORGAN VIDEO”. The law firm reached out to Disney about the video, making it clear they intended to advertise while also seeking confirmation that Disney wouldn’t sue them.

“Morgan & Morgan intends to broadcast the Advertisement nationwide over television, online, and through social media channels,” wrote Damien H. Prosser on behalf of the firm. “The copyright on ‘Steamboat Willie’ expired on January 1, 2024, and the property has, since that date, entered the public domain. We believe that the Advertisement does not violate any of the copyright rights that Disney originally enjoyed in and to the property.”

The Response to The Incident

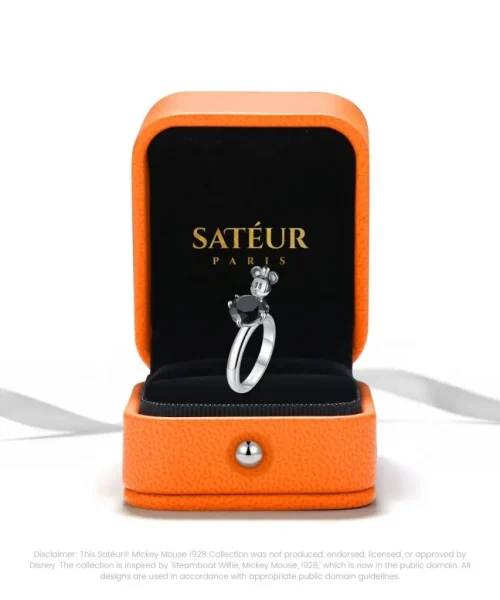

Disney did not give confirmation. “Disney’s policy is typically not to provide legal advice to third parties,” replied Gloria Shaw, Disney’s Chief Assistant Counsel. “Without waiver of any of its rights, Disney will not provide such advice in response to your letter.” Unwilling to release the advertisement and risk a lawsuit from Disney, Morgan & Morgan filed a lawsuit first in the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida, since its headquarters are in Orlando. The law firm was also established in response to Disney’s past “aggressive enforcement of intellectual property rights”, namely in July, when the company sued Satéur, a jewelry company based in Hong Kong, for allegedly selling “illegal Mickey Mouse jewelry” featuring the same character as the one in Morgan’s advertisement. The newest lawsuit stems from this, along with Disney’s inability to confirm whether it will sue Morgan over the ad.

What Could This Mean?

While the process is ongoing, the outcome can significantly influence how other companies utilize public domain properties for their own benefit—and how far companies like Disney can protect intellectual property before conflict escalates. It raises an important question: in today’s world, where human affairs and the internet are more connected than ever before, how do we find a middle ground between expanding our opportunities for innovation and protecting creative works from exploitation?