In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the foundation of education has undergone an intense shift, echoing throughout the behaviors and habits of students worldwide. From the swift change to remote learning to the slow return to in-person education, students of all age groups were forced to navigate through many obstacles, adapting their behaviors by unusual means. As classrooms reopened and routines evolved, the pandemic left a persisting mark on student’s lives, influencing a wide range of practices from study habits and social interactions to mental health, academic performance, and behaviors in general. To explore these shifts firsthand, a small-scale report was conducted, including interviews across six schools in the CNUSD district– ranging from elementary, middle, and high schools.

Large-scale studies note these transformations before further discussion into the observations of CNUSD-based educators on their students’ behaviors after COVID-19. A group of researchers writing for the National Institute of Health conducted a cross-sectional study on the impact of COVID-19 on the behaviors and attitudes of children and adolescents, finding that “…social restrictions needed to reduce the spread of COVID-19 have increased sedentary behavior, disrupted sleep patterns, and caused changes in lifestyles at home and outside, especially among children and adolescents.” Comparatively, the EAB, an education consulting corporation, organized a survey, extracting data from more than 1000 educators across 42 states, and found that approximately 70% of instructors reported a rise in disruptive behaviors in the classroom.

Now, zeroing in on the reports based on educators from six schools in the CNUSD district—Wilson Elementary, Temescal Valley Elementary, Citrus Hills Intermediate, El Cerrito Middle School, Corona High School, and Santiago High School—their responses provide a direct look into these behavior changes, the roots of the problem, and their effect on the Corona-Norco community.

Educators from each of these six schools were asked to discuss and answer the following questions:

- How have students’ behaviors changed from pre-Covid to post-Covid?

- How have academic efforts changed?

- Has there been any major changes in test scores?

- Which grade level would you say was impacted the most?

- What are the major gaps in learning due to this?

Elementary School Response

Leah Byrne, the Principal of Temescal Valley Elementary, observed that after COVID-19, “Some students became engrossed in social media and gaming during COVID, and it seems they have shorter attention spans. Shorter attention spans can cause students to become distracted and increase negative behaviors such as acting out, distracting others, and fidgeting in class rather than paying attention to instruction.” Byrne’s examination of her elementary students links the magnification of behavioral issues to shorter attention spans resulting from increased social media use. This rise in the reliance on social media, gaming, or devices in general could be attributed to the divergence from social interaction that came with the pandemic’s social restrictions.

Her response coincides with a study written by a group of researchers in the Department of Communication and New Media at the University of Singapore, finding that there has been a rapid increase (about 20%) in global social media usage after COVID-19 as opposed to before the pandemic. Another study by the Pew Research Center bolsters this correlation between social media usage, attention spans, and behavioral issues, as constant distractions are on and off one’s device. For instance, not only do the recurring notifications from one’s device and the various social media platforms serve as a disruption, but social media apps that were popularized during isolation, like TikTok, acclimate users to short content, thus decreasing their attention spans, and as mentioned by Principal Byrne, this paves the way for more behavioral issues within a prolonged attention-based classroom.

However, Temescal Valley Elementary’s principal sheds light on some of the positives that resulted from remote learning and increased reliance on technology when responding to the question concerning COVID-19’s impact on academic performance, finding that “There are positive changes,” and continues by explaining that, “Some students have found that post-COVID, they now have the knowledge and ability to access assignments online and this opens up the opportunity to reach their teacher and classmates more freely. They can utilize Google Classroom and other online resources to increase their academic knowledge,” she concludes by asserting that “Students are becoming more and more tech-savvy.” The pandemic allowed students to utilize technology within every aspect of their education; thus, Byrne suggests that the children in her particular school were positively influenced by the reliance on technology introduced during the pandemic, as it fostered greater collaboration, communication, and accessibility. She finalized this observation by finding consistent Temescal Valley Elementary School test scores. On the other hand, Amy Johnson, the Principal of Wilson Elementary School, finds contrasting results, seeing drops in SBAC test scores in ELA and math after COVID-19. She observed that “More students are behind due to COVID in 4th-6th grade. They expect teachers to do much of the work for them.” She elaborated further, “They do not have as much stamina as they used to. Chronic absenteeism has increased since COVID, too, and students are missing a lot of school and are missing out on academics.” Chronic absenteeism is a critical factor in poor academic performance and is distinguished by missing at least 10% of days in a school year. Chronic absenteeism limits one’s ability to keep up with the learning goals and pace of schools. To support this observation, Nat Malkus, a Senior and Deputy Director of Education Policy Studies, found an 89% increase in the number of students who were chronically absent post-pandemic.

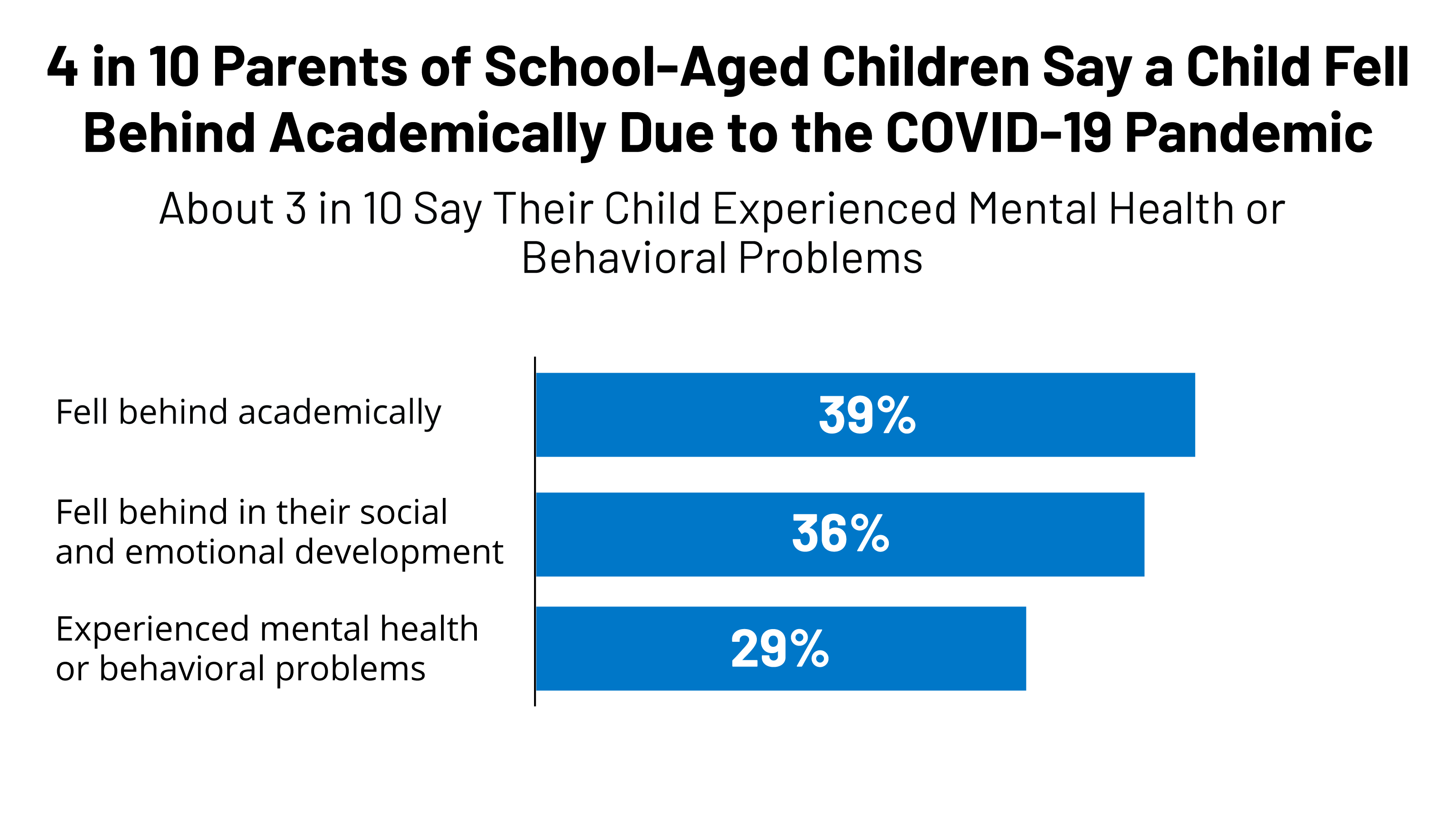

However, Principal Byrne and Principal Johnson’s observations aligned when they were asked which grade level was impacted the most– suggesting that younger students who did not receive preschool or the foundational kindergarten/first-grade in-classroom instruction were the most affected. “They missed out on a teacher in person teaching them the skills they need for a strong educational foundation. While online tools can be beneficial, the younger years seem to thrive with in-person instruction,” Principal Byrne elaborates. Johnson also agrees that this group of children was most affected by the pandemic as they missed a foundational period of hands-on learning needed to be successful. Lastly, Principal Byrne and Johnson emphasize that their elementary students are struggling not only with cultivating friendships, dealing with social-emotional issues, navigating conflict resolution but also missing phonic and basic math computation skills. Likewise, a national survey of instructors by Education Week established that 39 percent of educators reported a decline in interpersonal skills and emotional maturity after the pandemic. These skills fall along the lines of taking turns, listening to peers, and indicating self-control.

These observations largely coincide with the response of educators in later years.

Middle School Response

Principal Payne from Citrus Hills Intermediate School finds a common denominator with the elementary school feedback: residual Math and ELA gaps persist. Similarly, Principal Roberts from El Cerrito Middle School adds, “Our math teachers seem to think that our students have some gaps in a few key foundational skills (fractions, decimals, multiplication, etc.) that they should have learned during the remote teaching required during COVID.” Furthermore, a study by the Education Recovery Scorecard, the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University, and The Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University demonstrates that the gaps in learning that have grown wider during the pandemic remain today. McKinsey and Company conducted a report on three million students across fifty states and their i-Ready Assessment data, finding that many students are three months behind in reading and four months behind in mathematics. Payne also claims that literacy and numeracy scores have reflected knowledge loss worldwide. “Learning from home via Zoom during the pandemic set many kids back. There have been efforts to make up for time lost with extended learning opportunities such as after-school math and English Language Arts tutoring”, Payne says.

Focusing more on observed behavior changes, Principal Roberts from El Cerrito Middle School finds interchangeable results with the Elementary School’s Principals, emphasizing student’s difficulty with “dealing with minor conflicts between peers,” claiming that “What used to be a minor issue that could be addressed through conflict mediation seems to escalate much quicker into a more serious confrontation between students.” In support of this claim, data demonstrates that 1 in 3 educators reported a rise in aggressive behaviors and physical and verbal attacks within their students after the pandemic that still lingers today, although they are lessening. Not only that, but Roberts also touches on the topic of a loss of motivation “to preserve on tasks and assignments,” especially for students who had previously been struggling in school. “The gap between high and lower-achieving students appears to have grown,” he further elaborates. It can be concluded that a lack of motivation amongst students was a major disadvantage of the pandemic, as a lack of engagement or a sense of “ownership” and participation persisted even after remote learning.

Like Principal Byrne’s and Johnson’s response, Payne concludes by stating that primary elementary students learning to read and write were impacted the most. In contrast, Roberts deduces that their current 7th-grade class struggles more than previous classes. He provides a limitation to this observation as he cannot distinguish whether these issues are solely due to COVID-19 or due to these students being introduced to a new school. Nevertheless, Roberts did attribute the possibility of a decrease in test scores to students spending their late elementary years learning during the pandemic and missing some foundational math and ELA skills that may take a few years to recover. He highlights that the exact impact of COVID-19 on students will be unknown for a few more years.

That being said, the responses of high school educators provide a different yet simultaneously similar perspective.

High School Response

Principal Torres from Santiago High School begins by elaborating on the first two years back from COVID-19, “It was wild. It felt like lawlessness because students were so cooped up at home and finally felt free”, attributing this to the collapse of the regular structure that came with remote learning, “When you remove this structure there is chaos, and it was difficult to adjust to the routine and normalcy because we’ve never been in a place like this before.” Torres then emphasizes some of the behaviors and attitudes resulting from this, which were tardiness and restroom issues, which drove him and other instructors to implement stricter rules and policies. He was made aware of the complaints when first administered, which he retaliates by pointing out, “When running a school of thirty-six hundred, you have to have strict policies and rules to create order. Everyone may think they want to live in chaos, but they don’t because then things become unsafe.” He also highlights the success of these implementations, touching on the tardy policies, finding that tardy numbers have decreased by about 60% from last year after the administration of these rules.

To add a new high school-centered perspective, Principal Sanchez from Corona High School emphasizes that “Today, the one lingering piece I’ve seen is a lack of motivation and an apathetic approach to school. Students could be doing okay, passing their courses and earning credits, but they are apathetic about challenging themselves to take honors and AP courses.” However, before COVID, he elaborates, students were more motivated to take harder classes, “We had a lot more AP and honor courses than we do today,” he claims. Correspondingly, a licensed professional counselor and psychotherapist, Crystal Burwell, writes that “COVID led to many people experiencing cognitive overload, whereby our brains become short-circuited due to being inundated with information our brains are trying to process.” In other words, the stark contrast between workload from online instruction to in-person instruction caused many students to feel overburdened, thereby decreasing the motivation to challenge themselves further and take harder courses.

When asked which grade they thought was impacted the most, Sanchez observed holes in every grade level after COVID, as “Each year of learning is foundational for a student’s overall education, so missing out on one year of proper instruction can readily impact every student involved, no matter their grade level. Torres, on the other, opinionated that last year’s 9th graders’ behaviors were a reflection of the major impact COVID-19 had on their class in particular, “Last year’s ninth graders were the toughest 9th-grade group I’ve had in 20 years, we had the most expulsions, suspensions, and behavior issues with them.” Further bolstering this examination, Torres underlines that last year’s 9th graders did not experience that transition from 6th-grade elementary school to the foundational 7th and 8th-grade Intermediate school, “In 7th and 8th grade, a lot of teachers establish more structure and emphasize the importance of grades, and this year’s 9th graders were much more well-behaved because they still had that one year in middle school to have this particular interaction with adults.”

Academically, Sanchez and Torres agree that math test scores have dropped and that students still struggle with this subject today and most likely will for the next few years. This can again be attributed to the fact that math needs a foundation and builds off material learned in previous years. Over remote instruction, Torres and Sanchez concur that “it became too easy to cheat” and that “it was a byproduct of the way we were doing online learning,” thus paving the way for students to miss out on learning opportunities that were key to their math skills. On the other hand, both also discussed the positives that the pandemic brought, such as Google Classroom and Canvas, which created opportunities for students to access work without having to be in the classroom. Yet, as educators, Sanchez and Torres highlight the “missed opportunities” that they had, such as utilizing this tech-savvy and social media-focused generation to benefit students.

Concluding Discussion

Evidently, throughout all grade levels, from elementary to high school, the pandemic influenced many students’ lives, from social interactions and behaviors to academic performance. Each of the six head instructors of the schools found comparable observations of remote learning’s adverse impacts on attention spans, motivation, order, social-emotional issues, and test scores, especially in ELA and math. Various large-scale studies support these claims, and many agree that these behavior changes were a byproduct of the pandemic itself and the disorganization of remote learning that resulted in the loss of one year of an educational foundation. Specifically, those who missed kindergarten and middle school seemed to have been affected the most; however, every grade level was impacted in some way, changing the school dynamics and how educators might approach their students. On the other hand, isolation increased reliance on social media and technology more than before and introduced these new “normals” into education systems that positively influenced learning. Thus, COVID-19 brought along changes to students’ behaviors and academic performance in ways that may take years to bring back to normal, yet in the meantime, it continues to be addressed by educators not only in the CNUSD district and globally.