Question for any student readers: Did you go to El Cerrito Middle School?

If you attended El Cerrito Middle School, you probably remember the bins they had out during lunch – the plastic ones on the tables, filled with ice packs and lots of uneaten sides. If you didn’t want your carrots or apples, you put them here; if you did or even wanted more, you were free to take surplus. Simple enough.

Then you made it to Santiago. Chances are, you waited in line for lunch, got your food and sides, etc. – but what if you didn’t want some of your food, for reasons such as preference or food allergy, or whatever? You can give it to a friend who wants it, but that’s not always guaranteed; you can leave it somewhere, but would that not be considered littering? That leaves just one course of action: throw it away, because that’s all you or anyone else could do. That’s a problem, and only so many people are talking about it.

On December 15, 2022, fellow staff writer Larkin Fleming published a piece with similar issues to mine, titled “Santiago Food Waste.” In it she highlighted how students getting lunch are required to have at least an entree and sides of the students’ choice, but that, “Additionally, students are not allowed to just grab a side such as grapes or apples. If they want a side, they are required to receive an entree as well. Which also leads to a waste of entrees” (paragraph 2, sentence 3-5). Without a sufficient way to discard unwanted foods, students simply resort to tossing them into the nearest trash bin. So, how much are we throwing away?

It’s hard to tell, assuming you’re thinking about tracking how much our school specifically trashes lunch. Flemming found in her article that it was an estimated 530,000 tons a year for the majority of California schools, albeit for prepackaged lunches and aimed at advising parents. But what do the numbers look like when we replace prepackaged foods with school-provided lunch?

Artis Lay, writing for the Emory Economics Review in her article California’s Universal Meals Program: The Rise in Food Waste and Possible Solutions, brought attention to how California schools’ transition to free lunch catalyzed food waste in the state. Even before this change in the 2022-23 school year, she disclosed that California disposed of around 6 million tons of food waste every year; note that this figure also overlooks the impact of food waste on greenhouse gas emissions and, consequently, the environment as a whole.

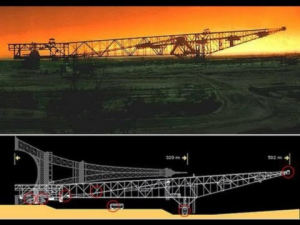

But regarding this amount, let’s try to put this number into perspective: the Overburden Conveyor Bridge F60 is the largest land vehicle on the planet – it’s a couple of hundred feet longer than the Empire State Building is tall and coming up on the height of Supreme Scream at Knott’s Berry Farm. Now take this vehicle, build about 44 more, and squeeze them onto an impossibly large scale as tightly as one can. Congratulations! You’re about 10% of the way there.

Or maybe something more familiar: if you were to cover an entire football field with snacks without stacking, you could fit at least 57 tons of food on it. If we allow stacking layers to fit 6 million tons, you would have to stack a bit more than 105,263 layers on top of each other – that would be a mountain standing about 2.5 miles in height, assuming the food is magically arranged in a cubic shape.

This was California’s annual number when lunch cost $4.50, meaning students had to be conservative with their food. What is it now that food is free?

Our school is one of many contributing to this crisis, so how can we do our part to lower that number? One strategy, as mentioned earlier regarding ECMS, could be the utilization of reusable containers. They’re a better option for the immediate disposal of unwanted items than trash bins, and with ice packs, they can keep refrigerated foods edible for hungry students. However, it’s not a perfect solution. Some time ago, during lunch, I brought this up to a custodian here, but he reluctantly brought up a point we haven’t yet considered: who’s to say students won’t just keep throwing away food? In other words, what obligation do a lot of students have to put food somewhere else when it makes no immediate difference to them whatsoever? This is not me being cynical – it’s just a realistic expectation I, among many others, have of people today, but I digress. So what else is there to do?

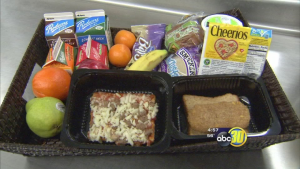

I was provided with another alternative by friends when I brought up this issue: removing the requirement for the packed lunch altogether. There’s definitely one way to go – if students can just refuse the sides they don’t want, then it doesn’t get thrown away, right? While this is sound enough logic, I personally disagree with it, mainly because the lunch provided is much healthier than vending machine snacks, with sides alone containing carrots, apples, bananas, and more. This is what the Healthy, Hungry-Free Kids Act of 2010 brought to American schools in the hopes of combating child obesity and set higher nutritional standards – making healthy foods optional, as I see it, would be a setback for the act. But kids can’t be forced to eat lunch they don’t want, so we’re back to square one, where food is being wasted again.

It’s very clear now that our school has a food problem, and there’s no easy or immediate solution – but that doesn’t mean we can’t work towards one. I have preferences regarding potential remedies (namely, reusable bins), but I doubt I have a comprehensive understanding of all the nuances surrounding this issue; that’s why we need to raise awareness about it and ideally discuss the best possible course of action. Whatever we decide to do, we have to improve how our school disposes of food – because if we don’t keep talking about this issue, don’t formulate a practical course of action, don’t encourage students to conserve their food even if they don’t want it, then it may not be long before the consequences catch up to us.